Cutting Your Losses

In sunk cost theory, we will often decide to stay with something because we’ve put time or resources into it. We believe that because we have “sunk” that cost into it, we somehow need to recoup it. That’s a fallacy.

– Jim Semick

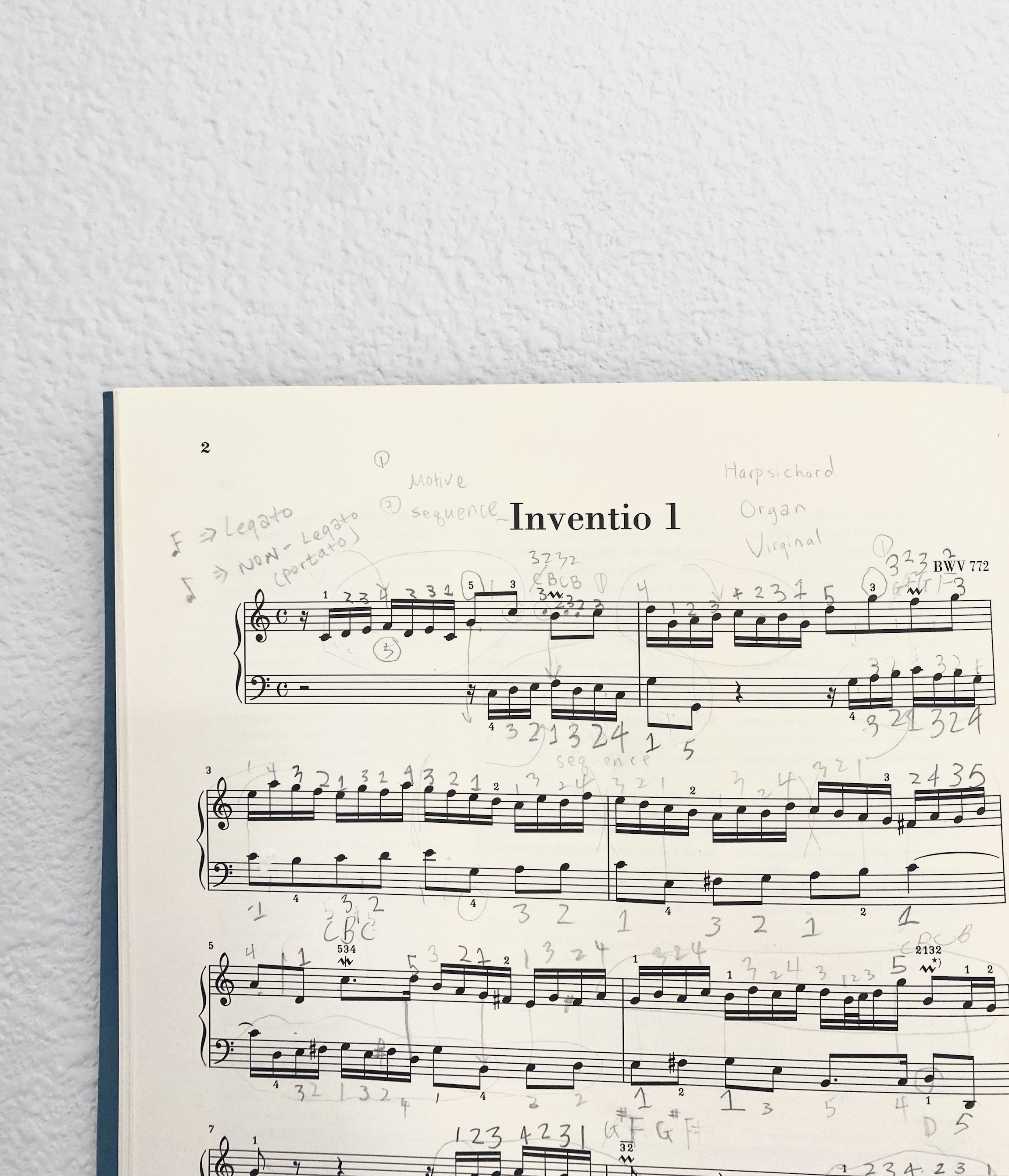

Yesterday, our nine-year-old son (the aforementioned Bach player) spent hours recording a submission for a piano examination. The guidelines required that he play through four performance-level pieces in one continuous video, and by the time he got that one magically good take, I had about decided that virtual submissions were a form of torture. Far better to do an IRL audition than face the endless possibility that you could still get a slightly better take, or to play three pieces with perfection only to make a stumble in the fourth. Frankly, our son handled it better than I did, figuring out early on that it was best for me to leave the room.

He finally got that good take, and we made the submission—only to discover that he was ineligible due to not having yet taken a music theory exam we had known nothing about. The idea of aborting everything really bothered me—because it wasn’t just the work of one afternoon, but of the better part of this year, work he would probably never get credit for.

It was hard for me to let go of that. And my frustration and anger, my obsession with finding some way to work it out despite the increasingly obvious impossibility of that, was making it hard for me to think clearly about how to move forward.

In other words, I got stuck in sunk cost. In economic terms, sunk cost is money that has already been spent and cannot be recovered; as such, it is theoretically irrelevant to future outcomes and should not be considered in future decision-making. The sunk cost fallacy occurs when people become tied to unsuccessful endeavors simply because they’ve already committed resources to it. This is continuing to play in a casino to recover money you’ve already lost, finishing a bad movie because you already paid for the ticket, not replacing an incompetent employee because you already invested in their training. In parenting, it’s making your child continue an activity that may not be a good fit because you’ve already invested in past lessons. Or in this case, making our son jump through hoops he may or may not want to do, simply to justify the work he’d already done.

But my inability to let go of sunk costs is about more than economic formulas. It has to do with my tendency to conflate process and result, to feel like all the work is only worth it if it results in an outcome that is visible to others. That is what motivates me, and so that is what makes what I do of value. I have a hard time parsing apart the result of the work from the reason I do the work, and so I will hang on and work for all the wrong reasons just to get that result.

My husband has less difficulty with this. It took him about two seconds to realize there was nothing we could do about the piano situation, to say with genuine feeling that he was glad our son had learned so many valuable skills in the process, and to pivot to what was best for him moving forward. He tells me this is because he has more experience with failure in his life. When you’ve failed a lot, he says, you get good at cutting your losses and moving on, at realizing there is more than one path to an outcome, at figuring out what kind of outcomes you really want anyway in life. You get better at being able to look back and say, I got something good from this—and then to move on.

So I stopped and tried to look back like that. I thought about seeing the score for the Kuhlau Sonatina for the first time and thinking our son could never play it, then hearing him go through the same runs by himself, over and over again, until one day he did. I thought about how his little hands engineered ways to reach chords too big for him. I thought about the three atlas books he sat on so that his feet could reach the pedal. I thought about the victory-fists he made after each song that got caught on the audition tape. And I thought about that moment after he finished, how he came out of the room cheering and jumping. Turns out, he doesn’t care at all that he'll never get to submit it or get an official certificate. He’s just happy he did it (and that he can now move on to other pieces).

The fact is, he likes to play because he likes to play. The cost is not all that sunk for him, because it was never about some piece of paper or a judge’s opinion. He does these exams, and yes, he might learn a little theory, to the degree that it makes him a more well-rounded player, but in the end it’s about the music itself. There is something right about that, something which the world has yet to spoil. Something from which I would do well to learn.