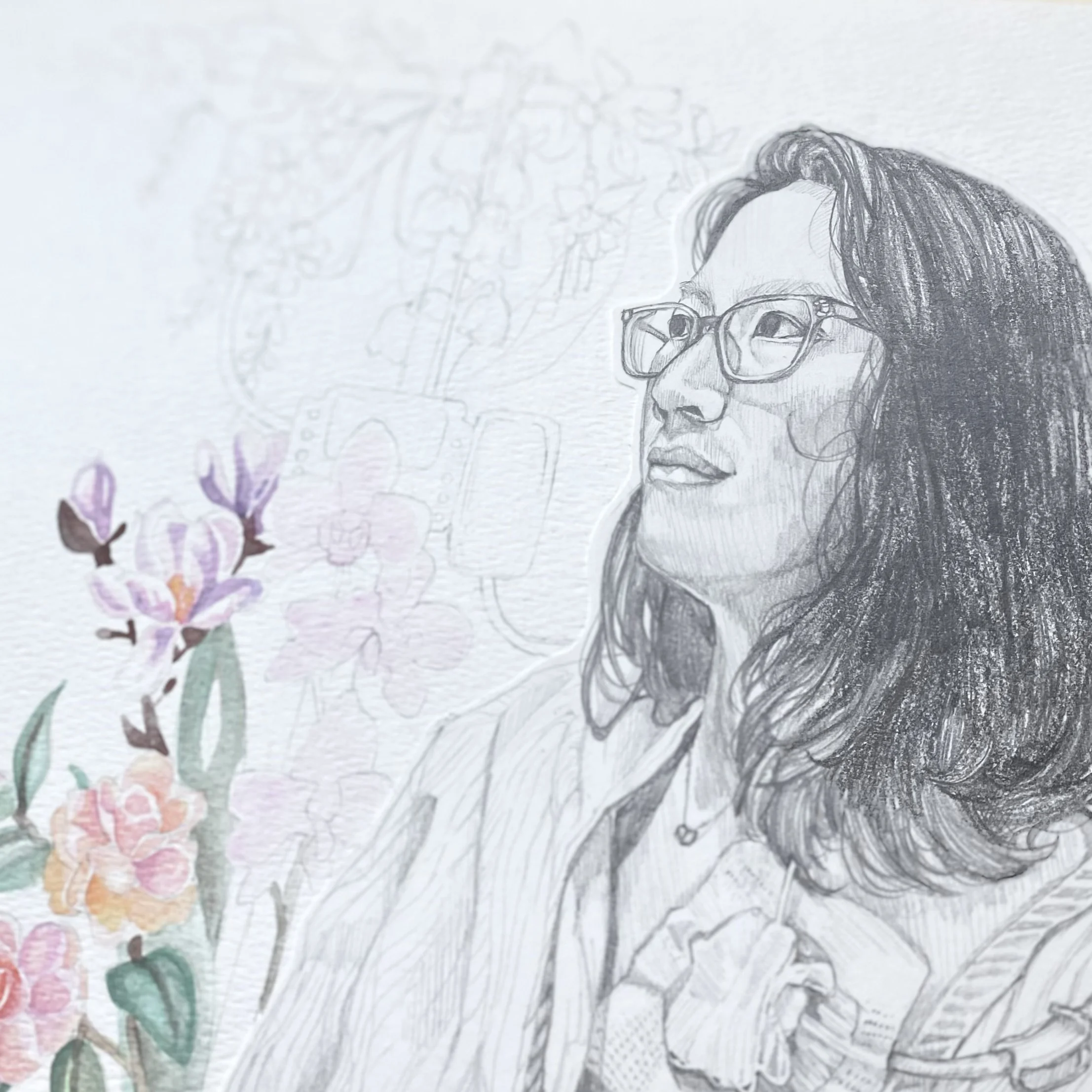

Ghost

It has rendered him a ghost of himself.

– Erin Morgenstern, The Night Circus

Earlier this week I had my second chemo infusion, which felt harder to face than the first, maybe because I knew what was coming. I used to wonder why people on chemo could not be more precise about what it is like, but now I see there is no word. Sick, drugged, achy, foggy, always that feeling in the back of your throat like you might throw up, as if your body is trying to eject something it knows should not be there—there is no word, and anyway you don’t feel up to trying to find one. Someone told me once that their father got to the point with chemo where as soon as they pulled into the hospital parking lot, he would break out in sweats. No words.

My oncologist, who keenly saw through my tendency to sugar-coat symptoms, dose-adjusted this time so the fatigue wouldn’t be as bad; that and the antiemetic pills took the edge off the worst of it, but there is no avoiding the no-words terribleness of it all, the slipping into an existence in which I become a ghost of myself, lost to the drugs. Sometimes I wake up and know it’s going to be a bad day; other times it hits me in an unexpected wave.

All along, I’ve still got one foot in regular life. Today, I got through taking a kid to a music lesson by nibbling on crackers to settle my stomach, but found the smell of the pizza my husband had baked for lunch too nauseating to tolerate when I returned home. One of the boys asked for help preparing for a piano competition (“sounds great” was about all I said); one of the girls needed assistance inventing a sandwich for a school assignment (apparently fig butter does not taste good with prosciutto, though again that could have been the chemo talking). Then it all got to be too much, I found myself wanting to rant about why there was always so much food lying out for our perpetually hungry kids, none of whom seemed to be cleaning up after themselves, and decided it was time to take a break and go pour myself a bath and have a proper cry. My husband came to sit by me. My body looks terrible, I’m crying. I feel terrible. I’m so tired of this cancer. You look just as attractive to me as before, he says. But I know it feels bad. You’ve been through a lot in the last four months. I stay in the bath, letting myself sink into the badness of it all.

After, I find my husband has taken the kids to the library and one of the boys now has a book of card tricks he’s excited to try out. Our youngest skips by in a pair of fluorescent magenta-pink tights, a color unlike any I own, but which somehow suits her perfectly. Our other boy asks me to text his friend so they can go biking and I picture them exploring the neighborhood together in the sun. Maybe it’s not so much that I haunt the world now, but that these good things haunt me, reminding me that it is not all bad.

One of my friends gave me a card on which she’d hand-drawn a graphic from Kate Bowler: Have Whatever Day You Are Having. Ordinary. Tired. Lovely. Mournful. Overwhelming. Painful. Garbage. For Others. Beautiful. Holy. These days, every day feels like all of the above—lovely in its ordinariness. Overwhelming in its mournfulness. Beautiful and garbage, the one all the more so because it exists in the shadow of the other. Wiman writes that we find God through “overmastering sorrow or a strangely disabled joy … it may be that the most authentic spiritual existence inheres in being able to perceive one state when you are squarely in the midst of the other. The mortal sorrow that shadows even the most intense joy. The immortal joy that can give even the darkest sorrow a fugitive gleam.”

Andrew Murray puts it this way: “[Christ] understood the paradox of the Christian life as the combination at one and the same moment of all the bitterness of earth and all the joy of heaven.” I find that the badness has not taken away my consciousness of beauty and joy, but rather deepened it. And my belief that joy will come in the end has not mitigated how tired I feel of what I and others I know are going through right now. I think of Jesus, weeping on his way to Lazarus’ grave though he knew he was about to raise him to life—he knew, yet not one word of reassurance did he utter along the way. He just cried with his friends.

Our son has learned a new magic trick. Pick a card, Mom, any card! And when he correctly guesses which one it is (I have to concentrate to remember it myself, must be the chemo brain), he yelps yes! yes! in unfiltered jubilation. It worked! And I smile. I’m going to have to tell him in a minute that I’m getting too tired to participate, but for now I smile and let his joy fill the room.